Before any oil flush project, it is important to set a cleanliness goal. Whether it’s a simple rinse/purge as part of a lubricant change, or a high-velocity oil flush after a major system failure, at the end of the process, you should be confident that the target system cleanliness has been achieved.

When we enter the planning phase of a flushing project with a customer, we help you establish cleanliness targets aligned with your goals and OEM specifications that meet ISO 4406 or NAS 1638 cleanliness requirements. After the process is complete, there are several ways to check that these targets have been achieved, ranging from simple visual inspections to laboratory analysis. Because contaminants come in a range of sizes and types, it’s important to address both the particles you can see with the naked eye and those you cannot. Often, the best approach is to use a combination of methods that provide accurate and reliable results without spending extra time or money needlessly.

Flange Screens

Generally preferred by oil flushing experts, flange screens (or slip screens) can be placed between two flanges in place of gasket material. This style of screen allows for the full-flow particle capture and multiple screens can be layered together.

Screens are a simple indicator of cleanliness. As they are coated with debris, they should be removed and cleaned to avoid the potential for fluid backup. By the end of a flushing procedure, screens should be looking clean and free of buildup. Since a screen is a frontline inspection location, it’s often helpful to add valves on either side of the screen to make it easy to perform spill-free inspections of your screens.

Strainers

Strainers, like filters, are used to remove contaminants as oil passes through them. Strainers are generally used to capture larger contaminants (40 microns or larger) but can also be used to check the cleanliness of oil. Because forty microns is generally the smallest particle size that can be seen by an unaided eye, strainers retain particles that will be visible to the inspector. There are a few types of strainers to consider using for inspections:

- Wye Strainers – These strainers employ a cylindrical screen for inspections. Care should be taken, however, as contamination can drop out into the screen cover, resulting in a false positive reading.

- Basket Strainers – These strainers are commonly used in oil flushes and have a sealed bottom that catches materials for inspection.

- Witch’s Hat Strainers – Less commonly used during oil flushes, witch’s hat strainers are often used in the return header to prevent contaminants from reaching the reservoir. These strainers are useful for the detection of gross contamination, but the screens have a tendency to tear.

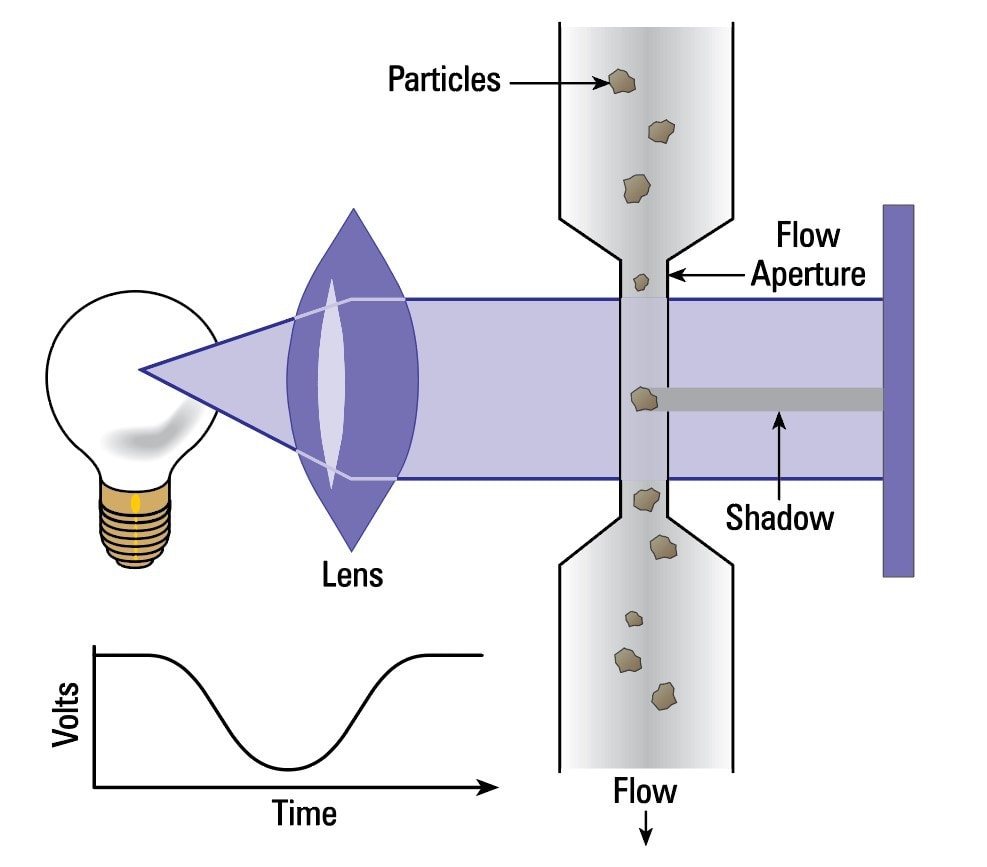

Portable Particle Counters

One of the most reliable ways to verify the amount of microscopic particles present in oil, onsite particle counters also provide the benefit of speed. Different types of counters are better suited for different applications. Light-refracting counters, for example, work well with turbine and hydraulic fluids but are often inaccurate when used with darker oils or oils contaminated with moisture. Pore-blockage counters, on the other hand, do work with dark or moisture-contaminated oils but are sensitive, requiring special care in terms of handling and calibration. High-quality particle counters will generally provide data for both the National Aerospace Standard (NAS) and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) cleanliness codes.

Bag Filters

Cheap and readily available, bag filters can be used like filters, in regards to inspections. Bag filters are nominal, however, meaning they do not capture all of the contamination. Additionally, they can present difficulties when inspecting and often have to be cut open to allow for a particle count.Laboratory Analysis

Laboratory testing offers the confidence of controlled and certified results. The downside of lab testing is the amount of time required to receive those results: You must collect a sample, package and send it, wait for the lab to test it, and then receive the final results; the process can take several days or even weeks.

Patch Testing

Patch tests are a quick way to determine particle counts in oil but are susceptible to human error. IF needed, the results of a patch test can be supported by further laboratory analysis. A patch test works by submitting a specific volume of oil to a membrane filter; the sample is pulled through the membrane with either an electric or manual pump.

The pore structure of the membrane prevents particles above a specific size from passing through, instead retaining them on the surface. Residual oil is then washed from the membrane surface with a solvent. Following this process, the membrane is inspected for discoloration and particle density. The sample can then be compared to standard patches of known contamination levels, determining the cleanliness of the oil.

Patch tests are relatively inexpensive, easy to perform in the field, and, unlike optical particle counting, patch tests allow for the inspection of organic particles, particle shape, particle color, and edge detail. For that reason, they are one of the primary methods we use in oil flushing projects.

How does IFM Verify Cleanliness?

We frequently use a combination of screen inspections and patch tests to verify system cleanliness during and after a flushing project. In most cases, a cleanliness target of 16/14/11 ISO 4406 has been set, which can be accurately verified by a patch test. In addition, we provide a comprehensive post-job report within 30 days of project completion that includes information on cleanliness tests along with all daily reports and related documentation. Third-party lab analysis is often included with this report including a laser net-fines and pictures from the patch test.

Whether you are considering flushing for a commissioning project, switching to a new oil, or addressing a maintenance issue, IFM is here to help.